By Karine Solnon

July 28, 2022

Visuals by Titus de Feyter

I. Introduction

The European gold and silver retail market has seen no reduction of the tax burden in recent years. In fact, all trends point to the contrary.

To invest in gold or silver as a private investor,1 you need to build a global view.

- Understand the implications of taxation regulations, both when you buy, and when you sell.

- Know the rules of the game of the precious metals retail market itself: the customs, the different parameters influencing the price, the fees, the hidden costs, and the restrictions that may apply.

- Finally, understand what role gold and silver may play in the future economic system.

II. Gold and Silver Tax Regulations – Buying

The European market applies a particular type of indirect tax on all goods and services called Value-Added Tax (VAT). Its mechanisms are mostly identical for all the 27 members of the European Union (EU). The tax is transaction-based and proportional to the price of all goods purchased.

Certain types of precious metals—depending on their purity, their form, or their function—benefit from either a total exemption or a special scheme (see Figure 1).

The United Kingdom and Switzerland are not part of the EU but apply similar regulations.

No VAT for Investment Gold

Since 1998 under the European VAT directive,2 Investment Gold can be purchased free of tax throughout the European Union.

Prior to that date, all gold transactions, with the exception of import and supply of gold by and to central banks, were taxable.3

Unfortunately, Investment Gold4 does not cover all forms of gold. Tax exemptions only cover:

- Gold bars or wafers with purity equal to or greater than 995‰5

- Gold coins:6

- with a purity equal to or greater than 900‰, and

- are minted after 1800, and

- have or have had legal tender in the country of origin, and

- are sold with a premium less than 80% of the spot price7

- Certificates for allocated or not allocated gold (certificated for bank deposit gold as owner of the gold or as creditor of the bank)

- Gold loans, swaps, gold future and forwards contracts.

The VAT exemption applies:

- to all purchases made within the European Union, or

- to Investment Gold imported by the purchaser in the European Union.

VAT on Gold Nuggets, Silver Bullion, and Silver Tokens

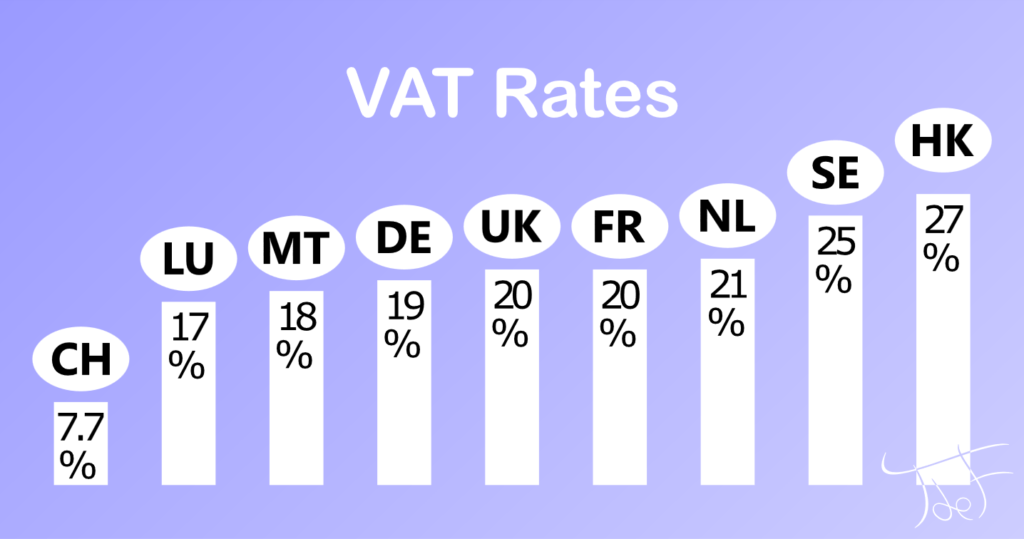

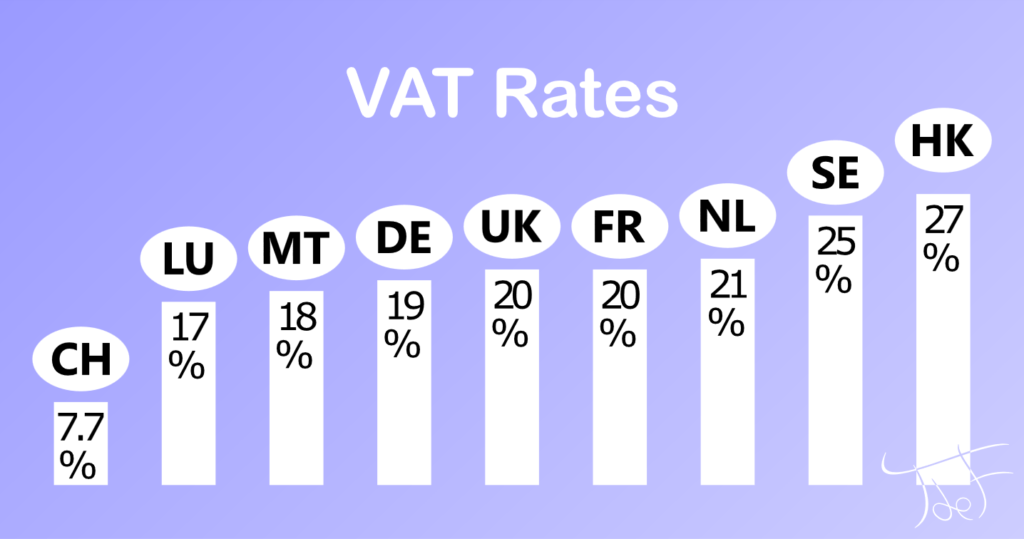

In all other cases, VAT will be charged and calculated as a percentage (VAT rate) of the price of the precious metals. The rates are different per country (see Figure 2).8 The lowest rate goes to Luxembourg with 17%, followed by Malta (18%), Germany (19%), France (20%), Netherlands (21%), Sweden (25%), and Hungary (27%).

If your country has a high VAT rate, you can buy gold and silver in either of the following ways:

- Buy online within the EU at a lower VAT rate, as the seller applies the VAT rate of the member state from which the goods are sent.9

- Buy outside of the European Union in countries like Switzerland (with applicable VAT of 7.7%) or Norway (with an applicable rate of 0% on silver coins), as long as you keep your purchase stored in that country or in a freeport to avoid paying the tax upon importation in the EU.

Until recently, you could also buy online tax-free investment silver in Estonia. However, Estonia abolished the VAT exemption in July 2022.10

VAT on Silver Coins

There is an ongoing debate regarding the taxation of silver coins. The EU VAT Directive of 2006 in its Article 135 e) exempts from VAT “transactions, including negotiation, concerning currency, bank notes and coins used as legal tender, with the exception of collectors’ items, that is to say, gold, silver or other metal coins or bank notes which are not normally used as legal tender or coins of numismatic interest.”11

Currency includes generally all means of payment and ways to discharge a debt valid by law (legal tender) or voluntary by agreement among a group of people (for example, tokens).

Even when a currency (whether or not legal tender) takes a physical form, as long as its economic function remains a medium of payment, its transfer cannot be seen as a supply and, therefore, is not subject to VAT.12 This lets the door open to the use of local currency based on silver tokens.13

The situation changes when a currency becomes itself the object of an exchange for another means of payment.

The European Central Bank (ECB), in an opinion dated August 23, 2011, expressed that “Member States shall take all appropriate measures to prevent discourage euro collector coins from being used as means of payments, such as ….issuance selling above face value.” If newly minted legal tender silver coins can in theory be used for payment, doing so must be discouraged.

Due to the fact that their market value is far in excess of their face value, silver coins used as legal tender can be used only for investment and not as a payment media. Based on this interpretation, VAT applies.

To benefit from the exemption of VAT, face value and market value would have to be similar, or the token would have to be used in accordance with the market value of its weight.

Furthermore, saving on tax may not be worth it if you are paying a high premium on the melt value.

The result is that the option of using silver tokens as a local currency remains open but must be done with care and after checking other applicable local laws.

Vat on Margin Only: Numismatic and Collector Coins

There is, however, a way to acquire silver with a reduced tax level. When precious metals take the form of a collector’s item or a coin of numismatic interest,14 dealers have the possibility of applying for the special scheme on second-hand margin goods.15 The tax is in proportion lower, as the VAT rate is only applied to the margin of the dealer and not on the entire price of the coin.

The interpretation of what is a collector’s item is not the same in all countries, but it is now common to be able to purchase under that scheme minted or crafted silver bars or tokens16 (France), imported silver coins that are imported from outside of the EU or purchased from a private person (Germany), or more generally demonetized silver coins.

III. Gold and Silver Tax Regulations – Selling

Tax-wise, it is equally important to know how you will be taxed when you sell.

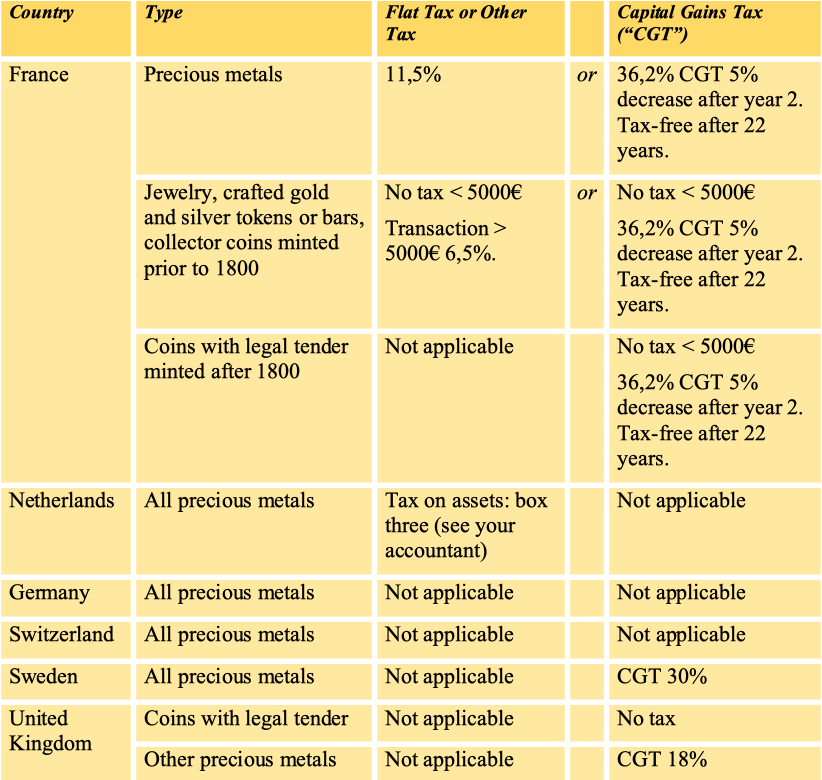

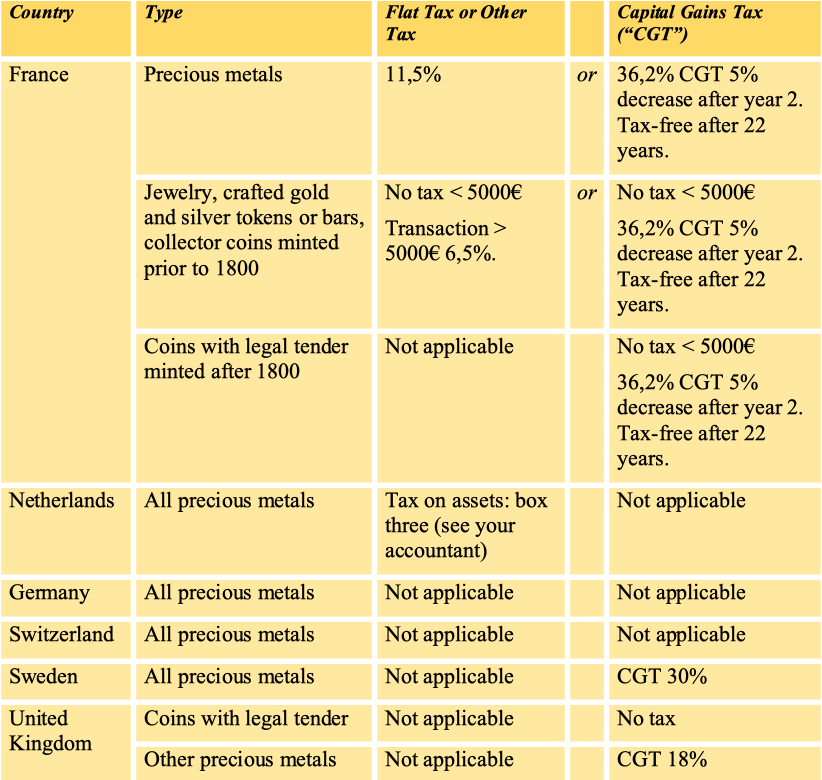

In that phase, the applicable tax regime is the one from your country of normal residence, in other words, the law of your tax residence. All 27 countries have their own rules.

An overview of selected European countries can be found in Table 1.

To calculate or benefit from the capital gains tax (CGT), a dated nominative invoice with a reference to the bullion or a dated nominative invoice sealed with the coins is necessary.

IV. Pricing, Hidden Costs, Restrictions, Market Trends

Investing in precious metals responds to the necessity to store for the future an excess of wealth that cannot be spent in the present while avoiding the hazards of fiat currencies.

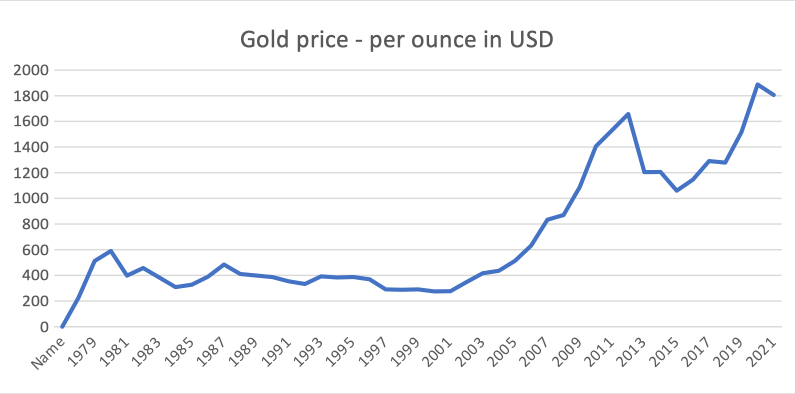

The physical gold and silver market is not for speculators. It is neither liquid nor exempt from friction. It is, however, a way to preserve wealth on a long-term basis from inflation, currency depreciation, and political instability.

Price and Premium and Other Costs

As for any investment, you need to be able to buy and sell at the right conditions.

The spot price of gold and silver is given daily either by the LBMA (London Bullion Market Association) or by the Comex (CME Group).

It is rarely possible to buy physical gold and silver at the spot price (save for gold-based contracts). In the retail market, a premium is added to the spot price. If it is not indicated, the premium applied by the dealer can be easily calculated by deducting the spot price from the total retail price.

The premium is not only the dealer margin; it is also influenced by the form, the market supply, the demand for a particular item, and the country of purchase. Comparing premiums is by far the better way to choose a particular product or a dealer.

Premiums have their own volatility. It is usually advised to buy the products with the lowest possible premium as their potential for increase is higher.17

Other costs may have to be added to the transaction, including postal costs, insurance, and storage costs.

Selling is often more difficult than buying.

Before buying, verify that the same dealer will buy the gold and silver back from you and confirm what they would pay if they were buying back at the same time you are purchasing. This will give you an idea of the liquidity of the product you have just chosen and the recovery period necessary to cover the transaction costs and related taxes. It will also make clear what conditions are required to maintain the value of your investment.

Be aware that it can be a long period before you can resell your investment in gold or silver for a profit.

Anonymous Transactions

Even if the regulations are getting stricter every year, it is still possible in Europe to buy and sell gold and silver anonymously with cash over the counter, but not in all countries.

In France, for example, cash payment for precious metals is strictly forbidden. Other countries have more flexible regulations.

You can pay in cash for gold and silver in the following countries:

- Germany: up to 1999 € (it used to be 10000€ prior to 2020)

- Belgium: up 2500€ per person and per day

- Spain: up to 15 000€

- Netherlands, Switzerland, and Luxembourg: up to 10 000€

And you can sell your precious metals against cash in the following countries:

- Germany: without limitation

- Belgium: 500€

- Spain: up to 15 000€

- Netherlands: 10 000€

Precious metals circulating within the EU above a value of 10 000€ must be declared to customs.

Freeports

Originally designed for the storage of assets in transit, freeports have become increasingly popular among taxaphobics and those wanting to increase their independence from the banking system.

Storing gold and silver in a freeport vault allows the investor to postpone the payment of the VAT on gold and silver until the time the metals reach their final destination to be sold.

The oldest European freeport is located in Geneva, but you can find them in many locations, including Monaco, Luxembourg, and Singapore.

You can store your gold and silver in a freeport for as long as you pay the custodian and storage fees.

Gold- and Silver-Backed Accounts

With the increasing fear of bank runs and bail-ins, gold-backed debit card companies have started to appear and are growing. There are now several companies in this market with different offers, marketing tax-free, liquid, and no-friction gold and silver.

They allow the buyer to invest in gold and silver and to convert the precious metals at the spot price into fiat currency through the use of a simple credit card. The gold can be allocated and is usually stored in a freeport.

Please make sure you do a complete due diligence, including the quality of ownership and management. As always, read the general terms and conditions carefully to verify the service costs and determine whether your deposit is protected in case of bankruptcy of the company.

V. What Role for Gold and Silver in the Future

The role of gold and silver in the future economic system will be influenced by recent and future regulations but also by geopolitics.

Central Banks Switch to Purchasing

Since the abandonment of the gold standard (in 1971 in the U.S. and in 1999 in Switzerland), gold has not had an official monetary role tied to the currency. Central banks started to use their gold reserves for gold leasing, a mechanism by which they would rent their gold to other institutions while keeping the same gold on their balance sheet. This led to serious rumors of gold price fixing.18 Considering the importance of their gold reserves, central banks had uncontested pricing power.

As mentioned earlier, the price of gold and silver is fixed at the London Bullion Market Association by five European banks19 based on their gold and silver contracts to be delivered within 48 hours. The spot price published by the Comex is defined daily on contracts to be delivered in the future at a set price. Both systems have been criticized as being overseen by banks themselves, not being transparent, being subject to manipulations,20 and not being free of conflicts of interest as evidenced by the numerous publications of the Gold Anti-Trust Action Committee.

In 1999, central banks signed the first Central Bank Gold Agreement21 limiting the amount of gold that central banks can collectively sell in any one year.

Prior to the agreement, the gold price was subject to sharp swings by central banks to maintain the price of gold at a low price.

Since then, the attitude toward Investment Gold has progressively changed.

Starting mainly in 2014, many central banks in Europe stopped selling their gold reserves and started to repatriate their gold stored abroad in their home country.22

In 2019, the ECB announced that the Gold Bank Agreements will not be renewed and further confirmed that central banks “had no more plans to sell significant amounts of gold,”23 confirming that “gold remains an important element of global monetary reserves, as it continues to provide asset diversification benefits.”

Since then, this trend has remained relevant.

The World Gold Council annual central bank survey 2022 shows that 25% of the central banks that responded have plans to increase their gold reserves over the next 12 months, listing as main reasons for holding physical gold in their portfolio: historical position, performance in times of crisis, long-term store of value, and no default risk.24

January 2023 – Basel III Implementation – Unallocated Gold Cost Increase

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) is an international financial organization owned by 63 central banks, among which the European Central Bank, the Federal Reserve, the Bank of England, and the People’s Bank of China.25 It was created under the Hague Agreement of 193026 and the constituent Charter of the BIS.

The BIS has a dual nature: It has the legal status of an international organization governed by international laws, but at the same time is funded through issued share capital as a normal corporation.

The BIS functions as a bank to the central banks. From 1950 to 1958, the BIS served as payment agent to facilitate bank payments and currency convertibility between European countries.

From 1962, it was the place where the G10 central banks discussed all arrangements made through the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to borrow among themselves and to maintain fixed exchange rate parity (GAB or “General Agreements to Borrow”).

The BIS27 also trades gold globally and confidentially. It is exempt from taxation and protected by its privileged legal immunity.28

The BIS hosts several committees. The most important is the Basel Committee for Banking Supervision (BCBS), created in 1974 to supervise the banking system following the bankruptcy of the Herstatt Bank.29

The Basel Committee is chaired by senior officials of central banks and by finance ministries. It elaborates accords (known “as soft laws”) that are not legally binding or enforceable but nevertheless are capable of exerting powerful influence over countries, public entities, and private parties. The BCBS decision-making process operates on a consensus basis. Governments and lobbies usually influence the content of the rules during the drafting process. The final draft has to be accepted by consensus by all members of the committee. Each country has a right of veto. Then, each member is responsible for implementing the framework into the legislation in its home country. The IMF and the World Bank then oversee member state compliance when reviewing a member country’s financial system.

In 1988, the BCBS introduced the Basel Framework to set a minimum standard for capitalization of banks. Originally conceived as a set of principles (Basel I, 28 pages), the Basel Framework grew into a more complex set of guidelines with Basel II, amended later on in response to the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 (Basel III, more than 1000 pages).

Among other policies, the Basel Frameworks define banks’ minimum capital requirements, the type of assets, and the weighting of risks to be set against them on the banks’ balance sheet. Each type of asset is weighted from 0% to 100% according to a predetermined perceived risk level. Originally, only cash and claims on central governments and central banks funded in national currency were 0% rated. Gold was weighted at 50%.

As of 2019, under Basel III, banks have been allowed to account for gold with a 0% weighted risk (allocated and unallocated).

However, from the first of January 2023, only physical gold held in the bank’s own vault and allocated gold will be given a 0% weighted risk.

Unallocated gold (such as options and derivatives) will have to be weighted at 85%, meaning that 85% of the value of unallocated gold will have to be backed up by additional reserves. In practice, bullion banks will have to hold more High-Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA) for longer periods of time to offset loans to their clients.30

As each country is introducing the Basel III Framework into own legislation, the introduction may occur at different dates.

In Europe, the Basel III Framework has been implemented by the EU Capital Requirement Directive (CRD) and Capital Requirement Regulation (CRR),31 and from there, into the member countries’ home legislation.

In the U.S., Basel III capital requirements are unlikely to enter into force before 2025.32

With the holding cost of unallocated gold becoming more expensive, it is expected that the demand for physical gold will increase, leading to problems of liquidity and increased gold pricing in the retail market. Gold mines that tend also to finance themselves with gold loans will find it more difficult to find financing.

In response to market concerns,33 the BCBS has announced that clearing banks could apply for an exemption for their unencumbered physical stock of precious metals, to the extent that it balances against customer deposits.34

The question remains as to why the BCBS is intentionally willing to restrict the bullion market and is making gold investment less attractive. Central banks also will be affected as the measure will impact their gold swap and gold loan trade.

The European central bank digital currency (CBDC) project was launched in July 2021. Holding physical gold and silver is a way for the population to ignore the digital currency and keep control of their finances.

Can the Basel regulations be interpreted as a way to put gold, together with cash, on the list of the next tangible assets to go, leaving no alternative to the implementation of the CBDC?

Gold as Part of Russia-China Growing Economic Cooperation

Since 2008, Russia and China have been buying significant amounts of gold35 and have increased their financial and economic cooperation. Russia’s central bank opened its first overseas office in Beijing in 2017,36 creating an institutional capacity to bypass the dollar and phase in a gold-backed standard of trade.

Currently, about $130 billion of Russia’s gold and foreign exchange reserves are in yuan assets.37

Russia and China are also two of the biggest producers of gold in the world. China has also been buying mining operations all around the world. The official figures attribute a reserve of 2300 tonnes to Russia and 1948 tonnes to China, but those figures could be below the reality.38

The latest figures for Russia are dated from the end of January 2022. In June 2022, Russia passed a law classifying the size of foreign exchange and gold reserves a state secret.39 So, it is unclear when the next reliable update will be made public.

Another important question is which strategic function the domestic gold mined in Russia will play from now on.

Two things have transpired over the past months.

First, the BRICS countries—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—are said to be currently discussing the setting up of a new global reserve currency40 with the possible creation of a common bank.41

Secondly, in a recent interview, Mr. Sergey Glazyev, a former advisor to the Kremlin, shared some insights about the design of another new digital monetary/financial system between the Eurasian Economic Union and China aimed at bypassing the dollar that could be built around a basket of national currency and a “price index” of important commodities including gold42 and precious metals.

Whatever the outcome, the increase in the Chinese and Russian gold reserves leads one to think that gold will also play a key role in this part of the world.

VI. Conclusions

In a period where the price of food is skyrocketing, the gold price remains surprisingly imperturbable.

The effects of gold and silver retail taxation together with the way gold is traded to the public have caused customers’ gold and silver investments to be treated primarily as an insurance function. As a result, securities, real estate, and other investments typically appear more attractive to the public.

At the same time, gold is growing in importance in the monetary and banking system, and the purchase of gold by central banks—benefiting from better liquidity conditions and several tax exemptions—is increasing.

The link between gold and the CBDC projects promoted by the BIS and many of its members is still unclear.

However, the trends in the regulations clearly show that access to gold for the public may be more difficult in the near future, increasing central banks’ power and influence even more.

With 36 000 tonnes, central banks are already holding one-fifth of the gold mined in history. It is, therefore, key to keep significant amounts of gold and silver inventory in private hands to maintain sovereignty.

The gold and silver markets are not as liquid for customers as they are for banks, but the underlying beliefs are the same. As the Dutch National Bank bluntly described it on its website in 2019:

“Gold is the perfect piggy bank. If the system collapses, the gold stock can serve as a basis to build it up again.”

Who would have guessed that central banks and us had so much in common.

Disclaimer: We hope that reading this article has helped you better understand the taxation and other practical aspects of precious metal market trends in Europe and given you some keys to further your personal research. We have made every effort to make sure the content of the article is correct, but we cannot give any warranty or representation that the content is free from inaccuracies or is up to date. Furthermore, please note that the content of this article is for general information purposes only and should not be relied on or treated as a substitute for specific financial and/or legal advice relevant to your particular circumstances.

Endnotes

1. Specific taxation regulations may apply to professionals.

2. Directive 98/80/EC amended by Directive 2006/112/EC.

3. Directive 77/388/EEC art 14.1 j et 15.11.

4. Art 344-356 of the VAT Directive 2006/112/EC.

5. Meaning that on a bullion of 1kg, you have a minimum of 995g of pure gold.

6. A list of coins corresponding to the definition is published every year by the European Commission (https://op.europa.eu/fr/publication-detail/-/publication/cbc68741-3c48-11ec-89db-01aa75ed71a1/language-en). American Eagle or Maple Leaf coins come into that category.

7. Percentage above which the coin is generally considered as a collectible or numismatic and, therefore, subject to VAT.

8. See https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-06/vat_rates_en.pdf and https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/taxation-1/value-added-tax-vat_en.

9. The VAT of the country of destination applies above a certain threshold.

10. See https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/ee/523042021001/consolide/current#para16.

11. VAT Directive 2006/112/EC Art 311.

12. Skatteverket v Hedqvist (C-264/14), 22 October 2015.

13. May be subject to other specific country laws.

14. VAT Directive 2006/112/EC Annexe IX Part B. Numismatic is defined as coins sold with a premium > 80% of the spot price. Collection: Commemorative coins defined as collection coins, Coins minted before 1800, CJUE (Affaire 200/84 ou arrêt Daiber : articles which are relatively rare, not normally used for their original purpose, subject to special transactions outside the normal trade in similar utility articles and are of greater value), Also definition of Art 135 VAT Directive. Additional local laws may apply.

15. The VAT Directive arts 311104 to 343.

16. Art 90 BOI-TVA-SECT-90-10-20120912.

17. See Jeff Desjardins, “How are silver and gold bullion premiums calculated?” (https://www.visualcapitalist.com/how-silver-and-gold-bullion-premiums-calculated/).

18. See “61. Note From the Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for International Finance and Development (Weintraub) to the Under Secretary of the Treasury for Monetary Affairs (Volcker)” (https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v31/d61) – ref Yannick Colleu, Investir dans le métaux précieux, p. 45.

19. ScottiaMocatta, Deutsche Bank, HSBC, Société Generale, and Barclays.

20. Gold anti-trust Action Committee (www.gata.org).

21. See “Central Bank Gold Agreements,” World Gold Council (https://www.gold.org/official-institutions/central-bank-gold-agreement).

22. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gold_repatriation

23. See “Central bank holdings,” World Gold Council (https://www.gold.org/goldhub/data/gold-reserves-by-country).

24. See “Annual central bank survey,” World Gold Council, June 8, 2022 (https://www.gold.org/goldhub/data/2022-central-bank-gold-reserve-survey).

25. In March of 2022, the BIS suspended the Bank of Russia (https://www.ft.com/content/c850eb36-c4d3-414d-a928-232cd1cafcd7).

26. See https://docs.pca-cpa.org/2019/10/1930-Hague-Agreement.pdf and https://pca-cpa.org/en/services/arbitration-services/bis/.

27. See “BIS gold swaps mystery is unravelled” (https://www.ft.com/content/3e659ed0-9b39-11df-baaf-00144feab49a).

28. Save for a limited number of cases – see Basic Texts, Basel, January 2019 (https://www.bis.org/about/basictexts-en.pdf). See also, Lisa Weeks, “The Argentinian Money and Banking Immunity,” Wall Street Journal, July 27, 2011.

29. See Charles Goodhart, The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision: The History of the Early Years, 1974-1997, Cambridge University Press, 2011.

30. See “Ross Norman – Basel III and gold – Central bankers locking the fire exits” (https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/ross-norman-basel-iii-gold-central-bankers-locking-fire-ross-norman).

31. Capital Requirement Directive IV 2013/36/EU and Capital Requirement Regulations (575/2013).

32. See “US banks anticipate delay to Basel III implementation” (https://www.risk.net/regulation/7947246/us-banks-anticipate-delay-to-basel-iii-implementation).

33. “Basel III capital requirements are unlikely to enter force before 2025 in the US,” industry sources say (https://twitter.com/RiskDotNet/status/1521448604782710785).

34. For a full analysis and access to the World Gold Council and London Bullion Market Association letter, seehttps://www.gold.org/goldhub/gold-focus/2021/06/basel-iii-and-gold-market

35. See “Russia Put in Gold” (https://www.sprottmoney.com/blog/Russia-Put-in-Gold-David-Brady-April-08-2022).

36. See “Russian cenbank says will open office in Beijing in mid-March,” (https://www.reuters.com/article/russia-cenbank-china-idUSL5N1GE2KU).

37. See “Shrinking Russia seeks China’s aid” (https://cepa.org/shrinking-russia-seeks-chinas-aid/) and Interview of Vasili Kashin in Novaya Gazeta (original text in Russian—translation by DeepL Translator) (https://novayagazeta.ru/articles/2022/03/03/nyneshnie-sobytiia-garantiruiut-pobedu-kitaiu).

38. On March 28, 2022, the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) announced a short-term fix of 5,000 rubles to a gram of gold (underneath the market value of 6000 rubles to a gram) following the announcement of the U.S. sanctions. At the same time, Russia announced that payment for oil and natural gas could only be made in rubles, forcing businesses to exchange for rubles to pay for energy. On the April 7, 2022, the CBR went back to gold negotiated price, but it was enough to start rumors about a gold-backed ruble. http://www.cbr.ru/eng/press/pr/?file=25032022_183346eng_dkp28032022_110644.htm#highlight=gold

39. See “State Duma passes bill in 1st reading classing info about size of Russia’s foreign reserves as state secret” (https://interfax.com/newsroom/top-stories/80540/).

40. See “BRICS: The new name in reserve currencies” (https://think.ing.com/opinions/brics-the-new-name-in-reserve-currencies/).

41. See “Shrinking Russia seeks China’s aid” (https://cepa.org/shrinking-russia-seeks-chinas-aid/).

42. See Pepe Escobar, “Russia’s Sergey Glazyev introduces the new global financial system” (https://mronline.org/2022/04/16/russias-sergey-glazyev-introduces-the-new-global-financial-system/); see also In Gold We Trust-Report 2022 at ingoldwetrust.report.

Bibliography and Recommended Sources

Alexander, Kern. Principles of Banking Regulation. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Bank for International Settlements. BIS Annual Report 2021/22. BIS, 2022. Available at https://www.bis.org/about/areport/areport2022.pdf

Capaccioli, Stefano. “VAT Taxation of Gold in the European Union.” EC Tax Review, 2014;23(2), p. 85.

Colleu, Yannick. Investir dans les métaux précieux: Le guide pratique complet. Eyrolles, 2014.

Haentjens, Matthias and Carabellese, Pierre de Gioia. European Banking and Financial Law (Second Edition). Routledge, 2020.

Lasok, KPE QC. EU Value Added Tax Law. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2020.

LeBor, Adam. Tower of Basel: The Shadowy History of the Secret Bank that Runs the World (First Edition). PublicAffairs, 2013.

LBMA Webinar series. Available at https://www.lbma.org.uk/videos/hot-topics-central-banks-silver-basel-iii.

OMFIF. Central bank digital currencies and gold: implications for reserve managers. London: Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum, 2021. Available at https://www.omfif.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Central-bank-digital-currencies-and-gold-1.pdf

Pengam, Franck. Géopolitique de l’or: Le métal jaune au coeur du système international. Géopolitique Profonde, 2020.

Stöferle, Ronald-Peter and Valek, Mark J. In Gold We Trust-Report (Full Version), 2022. Available at ingoldwetrust.report

Thieffry, Gilles. “Basel III and Commodity Trade Finance: An Update.” Journal of International Banking Law and Regulation. 2016;31(3), p. 124.

Wood, Duncan R. Governing Global Banking: The Basel Committee and the Politics of Financial Globalisation. Ashgate Publishing, 2005.

Appendix 1. Evolution of Gold and Silver Prices

Source: World Gold Council

Figure 1. VAT Taxation and Exemptions for Precious Metals

Figure 2. VAT Rates by Country

Table 1. Taxation on Precious Metals Sales in Selected EU Countries