“Sometimes, if you stand on the bottom rail of a bridge and lean over to watch the river slipping slowly away beneath you, you will suddenly know everything there is to be known.”

~ A.A. Milne, Winnie The Pooh

By Nina Heyn — Your Culture Scout

A.A. Milne was talking about an experience most of us will have had at some point in life—looking at a passing river from a bridge or its bank. That’s what mankind has probably done since the beginning of existence—stand by a river and watch it flow. Once, rivers were literally a source of nourishment, bringing in water and fish. Later, the direct connection to this source of life would break down for most people living in cities, only to be renewed occasionally by visits to holiday spots or when going fishing. For most city-dwellers, rivers and streams became places to visit occasionally or look at from a passing cart, train, or car when moving about the city.

Rivers, even if not immediately available or usable for everybody anymore, remained in our collective consciousness as a source of vital force and of connection with beauty, nature, or even divinity. All these connotations are represented in the famous Fountain of the Four Rivers at Piazza Navona in Rome. The four river gods presiding over the spouting water represent four major rivers of the world and, by extension, the four continents on which they flow: the Danube river in Europe, the Ganges in Asia, Río de la Plata in South America, and the Nile that flows across Africa.

For artists, river views have always offered a natural, picturesque subject, but every culture and every era has had different criteria as to what image would sufficiently convey the concept of a river.

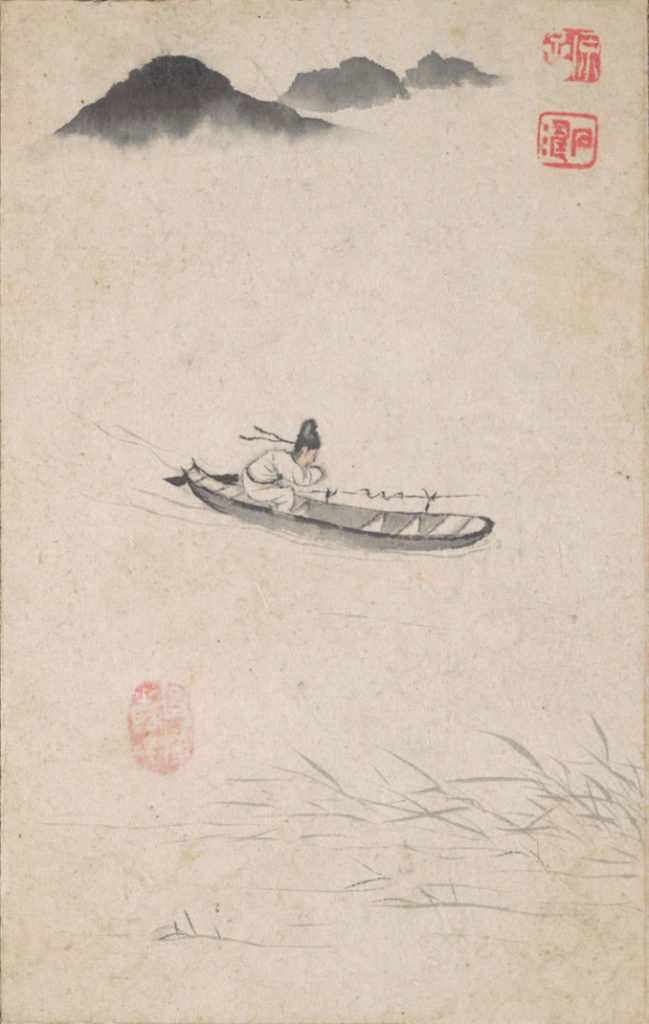

Chinese landscape art has different rules and assumptions from what a Western eye sees and accepts as visually correct. However, looking at this 17th-century painting by Shitao (石涛 is one of his names; it means Stone Wave, 1642–1707), titled Returning Home, both Asian and Western viewers can easily imagine the flowing river, even if it is mostly marked by the absence of lines rather than an elaborate rendition of waves. Ascetic though the painting may be, the title, coupled with the sense of forward movement of the boat, make this image very clear; a man is rushing down river toward home—real or metaphorical—with the barely signaled river as his road. Everything that needs to be said about human urgency and the river that enables it is said with the greatest economy of line. Less is definitely more here.

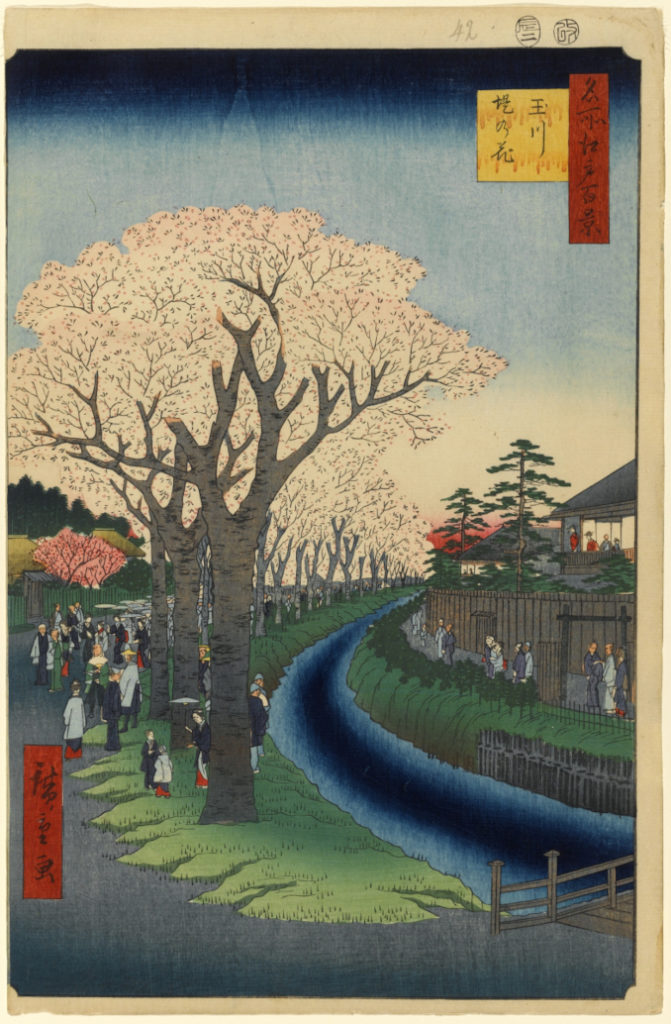

Art in Asia has always been more concerned with symbolic rather than any realistic representation. Thus, when Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858), one of the masters of Ukiyo-e—the Japanese genre of colored prints—created his One Hundred Views of Edo in the mid-1800s, he did not have to reject hundreds of years of realistic, Western-style paintings the way modernists in Europe had to do at the end of the 19th century. His river in Blossoms on the Tama River Embankment is presented as a variegated blue stripe in a composition of other strong colors, laid flat or with minimal, geometric texture. The result is a pleasing, vivid illustration, but the river is purely symbolic—this is not an image of an actual river, neither in color nor shape. But the curving shape and deep blue color is enough for a viewer—Asian in the 19th century or Western in the 21st—to identify this stripe as a river, even without the helpful title. Rivers, and especially their curves and the symbolic blue color, are embedded in our collective consciousness, no matter what style of image depicts them. Sometimes, even the color can be ignored if there is enough context.

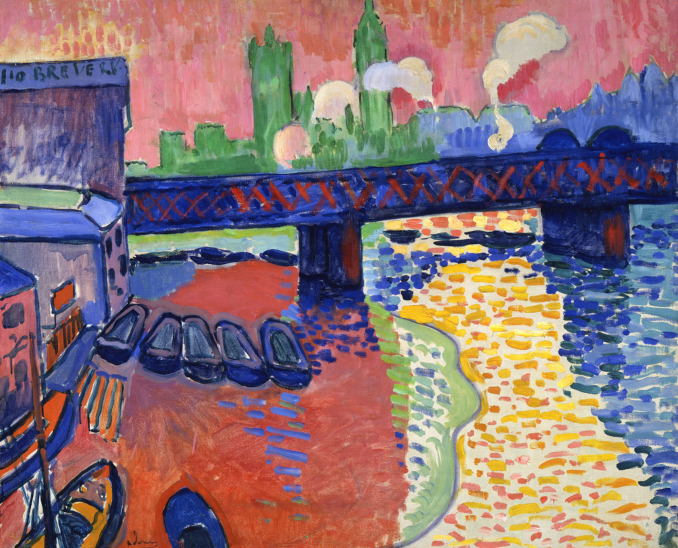

The Japanese flatness of surfaces and freedom of assigning any color value to natural phenomena inspired many art styles at the turn of the 20th century, including the entire Post-Impressionism style, Fauvism, Gauguin’s Synthetism, and the German movement Der Blaue Reiter. For André Derain (1880–1954) in his view of the River Thames in Charing Cross Bridge, the deep part of the river is all in shades of blue, the middle is golden, and the shallow muddy left bank is blood-red. When was the last time you saw Thames waters in these colors? But somehow, we recognize this is a river, partially lit by sunset in a mauve-hued sky, and we accept that while water may not look like that, it may feel like that, which is all that Derain was after.

Let’s swing back to an era immediately preceding Derain’s experimentation with color (ironically, by the 1920s, he had started painting in darker colors and a more realistic style). Throughout the whole long 19th century, painters may have been concerned with conveying a variety of ideas, but all tried to show nature “as it really is”—in styles that were later dubbed Naturalism, Realism, or even Impressionism. Let’s start at the beginning of that century.

For Romantics, all landscape elements—craggy rocks or peaks, huge oaks, a stormy sky, or water of any kind—could serve as metaphors for the vagaries of life, as reminders of death, as gestures of admiration of divine supremacy, or as illustrations of emotional upheaval. Although the unbeatable master of such dramatic and meaningful landscapes was Caspar David Friedrich, a young Englishman named Thomas Girtin (1775–1802) was able to tease out a great romantic image from the staid River Wear. His subject is a picturesque and imposing view of a large castle. Stones, unfortunately for the sense of visual excitement, do not move, but the river below them comes to the rescue—even if it has been regulated, bridged, and tamed for hundreds of years, Girtin is still able to extract the movement of the water at its descent, roiling dramatically in the foreground. Girtin died young (at 27, probably from tuberculosis), but he was a very promising watercolorist, both a colleague and a rival of JMW Turner (who apparently acknowledged his fellow painter’s talent with the caustic remark: “Had Girtin lived, I would have starved”). Girtin died in 1802 at the dawn of Romanticism, leaving behind dramatic and fresh watercolors of English ruins, castles, and meandering rivers.

No story on rivers in 19th-century art would be complete without taking a look at a canvas by this master of landscapes—John Constable (1776–1837). His “signature” compositions The Hay Wain and The White Horse, as well as this painting, View on the Stour near Dedham, were all painted within a couple of years, and they all feature the River Stour, about a mile from his birthplace. Constable painted six major landscapes of his native Suffolk, first doing oil sketches and then reworking them in his London studio. These full-scale oil sketches are now a very unique part of art history and are as appreciated as his finished works. While in the other two famous works, the river is in a way a setting for something else (a hay cart and a large horse), here, the winding river takes center stage. We can see it for miles in the distance, while the water’s luminosity, as well as the dramatic sky above, take on the grandeur of a Dutch Baroque landscape in the tradition of Jacob van Ruisdael.

Constable’s approach to landscapes—faithfully recording all details while augmenting them with narrative elements (such as a dramatic sky or some human or animal action)—has informed generations of nature artists all over Europe. In this painting, River Dunajec in the Pieniny Mountains, painted in the mid-19th century, the nature is majestic, the views spectacular, the rendition crisply photographic. This is painted in the tradition of Constable, with hints of the Barbizon school and even Thomas Cole and other portraitists of majestic landscapes of that century, except that it is the work of an unappreciated Polish artist, Józef Szermentowski (1833–1876). Szermentowski spent many years in exile, painting—from memory and from old sketches—nostalgic views of his fatherland. But this canvas was painted from nature during his brief visit to the limestone mountains of Pieniny. Szermentowski was on his honeymoon, and he was visiting one of the most popular summer holiday regions—no wonder that everything about this painting exudes calm and contentment. The flat, barely moving water is as inviting as it can be on a lazy summer afternoon. The people in the river are tiny compared to the mountains and the width of the Dunajec river, with their humble figures echoing the respect that the artist expresses toward the beauty and size of the nature he is portraying. Szermentowski’s life later dissolved into a string of illnesses and tragedies, and he died prematurely in exile and poverty. But for this brief moment in his life in 1868, he was able to commune with nature, drawing happiness and strength from the river he immortalized.

How different were the circumstances of young Thomas Eakins (1844–1916), who was not an impoverished political emigré, but rather a promising and energetic American artist, an avid photographer, and a sportsman. Following his return from a prolonged stay in Europe–where, like Szermentowski, he studied art in Paris–Eakins was reconnecting with his country and its landscapes. In his studies of competition rowing, Max Schmitt in a Single Scull being the first in the series, he included so many things that animated his life at the time–his love of sports, his joy at seeing his native land again, his pride at his skill (he painted himself in as one of the spectators in this and other rowing scenes), and his photographic-eye treatment of an image. The rower is his childhood friend Max (a lawyer and amateur sportsman), who won a prestigious race on October 5, 1870, and the boat is positioned exactly where it was at the finish line of that race. So, this is almost like a documentary record, except that it is painted with a poetic license, featuring the artist’s signature on the boat and Eakins himself in one of the boats. The most arresting here is the point of view—to look at Max, we are placed in the middle of this flat and glittering river. We are in the race, so to speak, and the river is as close to us as to the boaters. If this were a photo, the photographer would have to be positioned inside a similar boat, flat on the water, to get such a low angle.

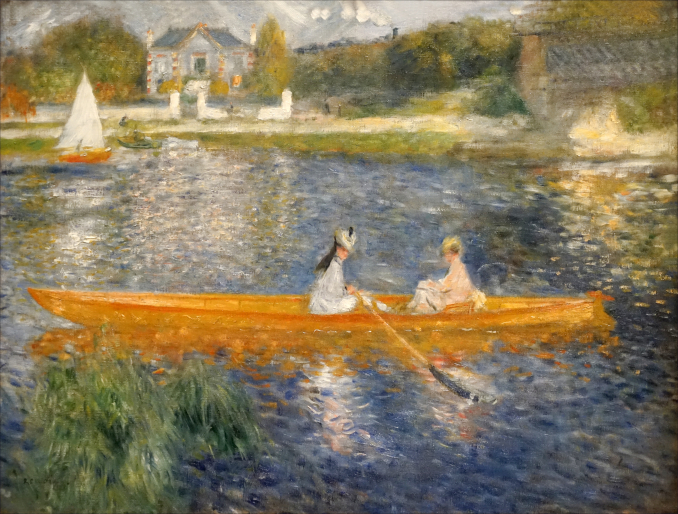

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s The Skiff/ La Yole is not achieved by such intimate communing with water. It has clearly been painted from either a bridge or a bank, and it is an entirely different approach to showing nature. For the Impressionists, showing “nature as it is” translated as painting the interplay of light and color on any surface, regardless of previous painterly conventions like naturalism, the blending of shades, or gradual color transitions. Impressionists were trying to capture the ever-changing light, regardless of what was being painted. Water, which changes color and shape with every movement, was particularly challenging.

The Skiff is famous in art history as an example of a technological change—the artist used new, synthetic pigments (cobalt blue and chrome orange), applying them straight from a tube (another technical innovation from a few decades before) and not mixing them, creating a strong color contrast. Technicalities aside, though, this is Impressionism as its best. The river’s waters shimmer and reflect; the out-of-focus silhouettes of the rowing women divide the image horizontally, while not distracting from the star of this picture, namely, the dark blue surface of the water and the way it reflects the orange boat and white dresses.

While European rivers, especially those accessed by painters living mostly in cities, would have been rather tame, flat, fairly narrow, and long subdued by urbanization, you could still find large and wild waterways in the New World. Let us take a look, then, at one of the visually most dramatic rivers that separates the United States and Canada through the wide basin of Niagara Falls.

The life span of Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900) encompasses the end of Romanticism, the explosion of industrialization, and huge political and social upheavals in both his native United States as well as the Europe and Middle East that he extensively visited for years. The massive works Niagara Falls from the American Side (1867) and its earlier companion, the 1857 Niagara, were painted for large audiences visiting a display and paying an entrance fee—this was a time when the more realistic and bigger a canvas was, the better its commercial prospects. By the end of Church’s life, however, art styles had splintered into dozens of movements, one more radical than the other, and such monumental and realistic works went out of fashion.

This painting, and even more so Niagara, which is proudly displayed at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, came back into viewers’ good graces thanks to their subject—the spectacular falls are a perfect symbol of American grandeur, in every sense of the word. Here we have a river at its most powerful—wider and steeper than any European river, and wild and vast like the American freedom that Church was indeed trying to convey. He painted this right after the Civil War, where he was a Union supporter, and it is considered his celebration of what he viewed as the war’s just cause. Church started to travel extensively soon after the war, launching himself into artistic explorations of Middle Eastern deserts and Greek and Syrian ruins. In all of these works, Church’s romantic soul was unmistakable—he always sought the dramatic vistas, the majestic skies, and towering stones. But before he got the Orientalist bug, he painted this American river as majestically as it deserved—miles of rushing water and swirling mist. Niagara is still a life source for two countries, providing hydroelectric power since the turn of the last century.

A landscape artist can be equally happy with a river that is a quiet local waterway or a gushing mountain stream—no matter, as long as the presence of water gives him a chance to say something he considers important, whether communicating an idea, a metaphor, a solution to a color or composition problem, or a particularly eye-pleasing view of nature. For the modern viewer, the original idea or mood of a painter when he raised his wet brush may be lost by now, but the subject remains—looking at rivers evokes in all of us that primal feeling of connecting with a life source. A river can be painted with the naturalism of Church, as an impression like the rivers of Renoir or Monet, or just hinted at, as in Asian images, but a river is always a connection to our instinctive search for nature.